Encounters

Barbara Bash writes these words from the Vidyadhara's will

I first met Chögyam Trungpa in 1970 and arrived at Naropa Institute in 1976 to teach calligraphy and book arts.

During the following years, I developed a big brush contemplative practice from his teachings on heaven, earth and human. I continue to find my creative way guided by these ancient principles.

Recently I began to write down the stories of my encounters with Trungpa Rinpoche involving calligraphy and artistic expression. In the process of telling these stories I am understanding more fully the impact he had on my life and the bravery that was stirred within. May you take them in and contemplate the encounters with your own teachers and how they have marked you .

Memories

-

In 1980 I was thirty two years old living in Boulder Colorado, teaching calligraphy and book arts at Naropa University and working as a freelance calligraphic designer.

I was also deeply involved in the world of Chögyam Trungpa, a Tibetan buddhist teacher who had arrived in North America ten years earlier and gathered a lively and diverse community around him. During the spring of that year I traveled to the Bay Area to assist in a Dharma Art seminar that Trungpa was offering in San Francisco. There would be a number of creative events happening - poetry readings, art and music performances and environmental installations. Since I had lived in Berkeley during the 1970's I had old friends in the area and it felt like a kind of return.

At one of the large public talks I had been asked to assist Trungpa with a demonstration of calligraphy. He would create spontaneous brush strokes during the talk to illustrate his teachings and these strokes would be shown with an overhead projector onto the large screen on the stage.

The hall where this was taking place was in downtown San Francisco. It had been built around the turn of the century and was decorated with antique sconces, patterned walls and carpet and held over eight hundred people. I had invited some of my friends from Berkeley to attend. This would be their first experience of the man who had become my spiritual teacher.

During the afternoon of the event I went out to gather the supplies for the calligraphy session. I had been told that Rinpoche (an honorific title) would be bringing his own brushes. I needed to buy a bottle of Japanese sumi ink (made from the soot of pinewood, animal glue and perfume) and a number of clear acetate sheets that would take the ink well.

I had received no instruction as to how many sheets would be needed. I decided to buy twenty-five. That seemed like more than enough.

In the late afternoon I returned to the place I was staying and got dressed for the evening, putting on a simple blue dress with a few colorful parrots embedded in the deep tone of the fabric. The man I was staying with, an inventive letterpress printer I had recently become enamored with, decided at the last minute not to accompany me to the event, so I headed out on my own.

When I arrived at the hall the large room was empty and I went back stage to get set up. When my preparations were complete I sat down in the back to wait. I had been told that Rinpoche had arrived and was in a private room somewhere in the building. At one point his personal attendant came over to me and said quietly, " He's in a very unusual state this evening. " I nodded, but had no idea what that meant. I did know that Rinpoche was an unpredictable person, sometimes arriving hours late for a talk, sitting down in front of an audience and saying nothing, or engaging people in spontaneous exchanges of poetry and song that sometimes took wild turns. Taking in this current report, I decided all I could do was hold steady and watch for cues of what was needed. Staying precise and contained seemed like the safest approach.

As the hall began to fill up I moved to the front of the stage, placing the bowl of ink on the table to the right of Rinpoche's chair. This table also held the overhead projector. His attendant brought out the Japanese brushes and brush holder and I arranged it all so he could reach them easily. I put a large flat cushion on the floor to the right of the table. This is where I would sit. I placed the stack of acetate sheets close to me on the floor.

By this time the hall had filled up and people were chatting and anticipating Rinpoche's arrival. Everything was ready.

I knelt on the cushion Japanese style with my legs folded under me. I looked out at the audience and noted that the friends I had invited were sitting in the front row. I smiled at them and they smiled back.

I waited, my eyes cast down, listening. And then I heard the sound of footsteps approaching. There was an uneven and recognizable rhythm to those steps. Rinpoche walked with a strong limp because of an auto accident fifteen years earlier that had left one side of his body paralyzed. He always had an attendant walking along side supporting his weight and holding his arm firmly. They crossed the stage together and he sat down slowly in the chair. He carried a Japanese fan in one hand which he put on the table. A glass of sake and a napkin was also added to the table. Rinpoche studied the whole arrangement and then slowly turned and looked out. There was something dense, immovable and quiet about his presence, his body, the space around him. The audience was silent. He turned his head towards me slightly. I made a small bow.

The evening began. I don't remember what he spoke about at the beginning. My attention was so focused on when I would need to move into action. Eventually that happened. Rinpoche turned to me and indicated he was ready and I placed an acetate sheet on the projector's flat surface. He picked up a brush, dipped it in the ink, gently wiping the excess off on the edge of the bowl, and slowly lifted it over the acetate, pausing for a moment and then landing, sliding, making a smooth elegant mark on the slippery surface. He turned his head to see the image projected on the big screen and smiled. After some moments he indicated for me to remove it and I carried the wet glistening sheet to an open space on the floor and placed a new sheet on the projector surface. Things were underway.

At some point Rinpoche began to speak about not trusting one's innate worth, of being embarrassed by who we are. He made a dense overlapping stroke that nearly blackened the entire sheet. Laying down the brush he turned back to the mark and said "Looking at what I've done, I feel so ashamed." As he spoke these words he reached out and wiped his hand in the wet ink, then softly slapped his cheek, drawing his hand across his mouth and leaving a large swath of blackness behind. There was an intake of shock and then laughter in the room. But I froze. I had not seen this coming. I didn't know what to do. Should I get up, find a paper towel, wipe his face, clean him up? Should I pretend it hadn't happened, just carry on? A long moment passed. My precision, my carefulness became solidified. I sat there, eyes down, doing nothing, in front of everyone.

Then I heard footsteps. Osel Tendzin ( Thomas Rich, RInpoche's successor and dharma heir ) arrived with a paper towel, bent down and gently wiped his teacher's face clean.

The evening continued.

Rinpoche engaged the audience that night in ways I'd never seen before, entering into lively dialogue with individuals, calling them out with intensity and delight. The energy was alive, compelling, confusing, wild. He was playing with the space and everyone in it. At one point he invited people to come up on the stage and make a brushstroke and I remember one fierce young Italian women who brushed out a huge NO ! as her personal expression to the world. I was moving quickly, catching and laying out more and more inked sheets on the floor. At one point I glanced out at my friends in the front row. They looked to be in shock.

Eventually the evening began to move towards a close and Rinpoche announced that we would end by singing the Shambhala Anthem together. The singing began - In heaven the turquoise dragon thunders . . . his high voice leading the chorus. As the song rolled along he speeded up his brushstrokes, creating a calligraphic expression for each line. At one moment he was moving so quickly I didn't get the new sheet of acetate down before his brush landed and the ink went onto the plastic surface. I jumped up, grabbed the napkin from the table, wiped the panel clean and placed a new sheet. There was no hesitation. I was riding the energy and knew what to do.

But now I 'm watching the stack of acetate sheets dropping lower and lower. The singing went on and the brushstrokes continued, fast and wet and bright. As the last line was sung I placed the last sheet on the projector surface. The final stroke was made. The song was done.

Much later that evening I returned to the apartment where my companion was waiting. "How did it go?" he asked.

I looked at him and said, " It was unusual, hard to describe. "

I realized at that moment we had nothing in common anymore.

And as I got undressed I saw that my blue dress had been sprayed with delicate black stars.

-

In 1978 I was living in Berkeley California and working as a calligraphic graphic designer. My studio was a sunny corner room on the second floor looking down on the university and town. This was in the Odd Fellows Hall building that also housed the Dharmadhatu Meditation Center. It had large gathering spaces, well worn brown painted hallways and a kitchen with appliances from the 40's, dimly lit and lined with long dark tables and benches. This kitchen space was where our meditation community hosted a demonstration by a young Korean calligrapher. It seems a more appropriate space would have been the bright colorful shrine room down the hall. Perhaps the calligrapher had requested to work at a table and chair. So there I was, part of a small group that had gathered in this space to observe.

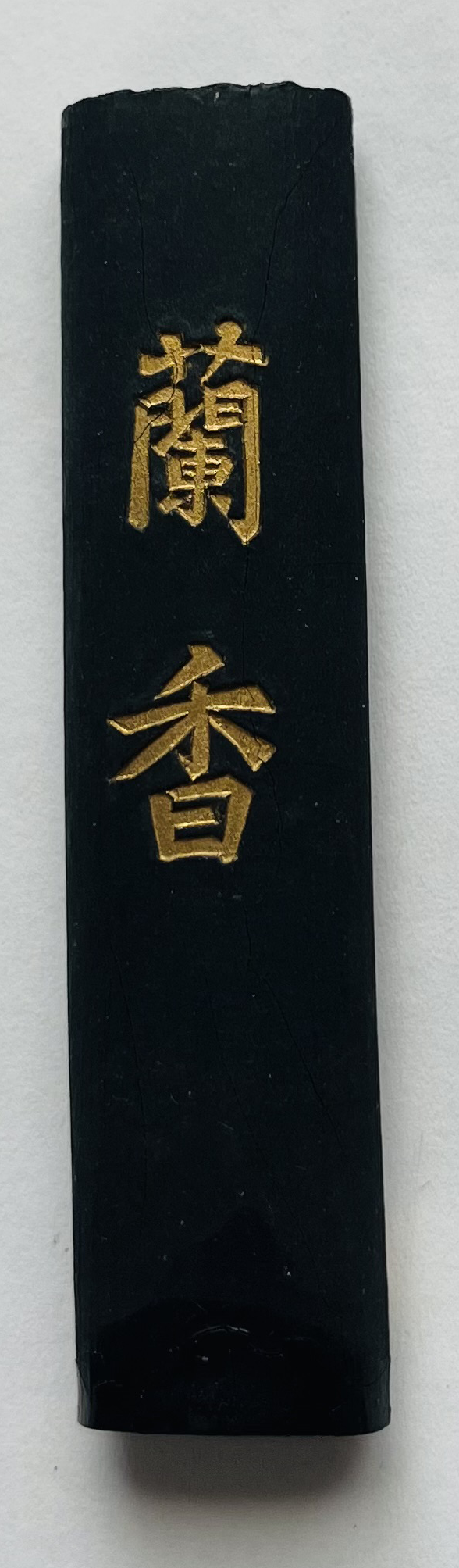

The calligrapher was in her twenties and beautiful, her oval face clear and open with gleaming black hair pulled back into a single braid. She wore a grey cotton robe that crossed in front and tied on the side. In the flurry of arriving she seemed nervous, talking fast, moving around. But when she had her paper laid out and brushes ready, she quieted and began to grind the ink, pulling the large black stick back and forth across the dark smooth surface of the rectangular stone.

I was familiar with Chinese ink sticks, the traditional painting medium that holds liquid ink in solid form and produces the pure black pigment for traditional Asian painting and calligraphy. Ink sticks dated back over twelve centuries in China, and had been made first with minerals, then with the residue of burned pine, and now with oil soot. The soot was mixed with animal glue and perfume and often carved with poems and delicate landscapes.

I had never seen a stick this large, two inches wide and nearly eight inches long. Holding it vertically with slender fingers, the young woman moved the dark form over the stone surface, leaning in, pulling back, her body following the rhythm. She paused every so often and added drops of water from a small jade pitcher to moisten the pigment, and gradually the black liquid began to gather in the deeper reservoir at one end of the stone. As the pigment dissolved a perfumed scent rose and drifted into the space.

We watched her act of preparation in silence. Her eyes were half closed as the stick and her body moved. As I sat there taking it all in, I could feel a tide of inadequacy rising inside. How sacred and spiritual it all was. I was a Western calligrapher, schooled in the alphabet, witnessing an ancient Asian ritual and the comparison left me small and deflated.

I felt outside this exquisite world, unable to join in. I had been born in a different culture.

My Tibetan teacher and calligraphic mentor Chögyam Trungpa had traveled to the West, bringing ancient teachings with him, but in the transplanting of buddhism to a new culture some elements had dropped away. He had taken off his monk's robes and married, he taught in colloquial English, and when he did calligraphy he did not grind his ink, he poured it from a bottle.

The Western alphabet was my visual world. Letters were so deeply familiar they moved and expressed through me naturally. But descriptions of Asian calligraphy spoke of the inner alignment and the synchronizing of mind and body. Brush styles expressed the energies of the natural world. Writing could be bold and thick as a cloud, delicate as an insect's wing, fluid as a bird in flight. I was captivated. But I was not Asian. I had my stake in the West.

A year later I moved to Boulder and began offering calligraphy classes at Naropa University. At some point I asked Trungpa if it was appropriate to be teaching the western alphabet at a buddhist college and he had said, "You start with your own tradition, dive down deep, and that will lead you to everything."

Now when I think of that ink grinding moment I smile. There was no way I could match it and no need to try. I have my own path. Now I find a settled mind as I pour the black ink into a white bowl, dip the brush, form the point, take a breath, and begin.

-

I am standing in the second floor hallway of Dorje Dzong, the large historical building in downtown Boulder, Colorado that is the center of Chögyam Trungpa's buddhist community.

It is 1981. I am part of a small group of people waiting to be brought into A Suite, the private office of Trungpa Rinpoche. I am feeling excited, assuming I am about to receive an honor and anticipating what is about to unfold.

During the years that Chögyam Trungpa taught in North America (1970 - 1987) he conducted many Refuge and Bodhisattva vow ceremonies. The Refuge vow is a traditional expression of a student's decision to step onto the buddhist path. The Bodhisattva vow is seen as an acknowledgement of the student's deeper commitment to engage with the world and place other's enlightenment before one's own. During this process the student receives a dharma name from the teacher. For the Refuge vow this name is said to be an expression of one's essential nature. With the Bodhisattva vow the name describes a quality that one could aspire to.

Other TIbetan buddhist teachers conducting these vows in the West had the Refuge names written on small pieces of paper and handed to the students as they came up to receive the teacher's blessing. With Trungpa the presentation of the names was a more complex process that involved the creation of an original calligraphic certificate. After a brief interview Trungpa would write the student's new name in Tibetan with a pointed brush. The transliteration and English version would then be added to the page by a Western calligrapher writing with a small broad edged pen. Trungpa would sign each certificate and an assistant would press the imprint of his family seal in vermilion ink next to his signature. At the end of the public ceremony the new refugees and aspiring bodhisattvas filed up, bowed to the shrine and then to Rinpoche. He would read aloud their dharma name in Tibetan and English and hand them this page of beautiful original calligraphy.

One year there were over two hundred people taking the vows and I was writing out the names along with a few other calligraphers in the buddhist community. A man named Robert had been a student of calligraphy for many years and worked in a traditional style. He wrote slowly and carefully and was shy, older than me, a bit awkward, withdrawn and humble. I was deeply practiced in these traditional scripts and was also exploring looser writing with larger brushes. I relished the precision of pen scripts, and loved being a part of these vow certificate creations. I was also stretching into new calligraphic expressions, feeling confident and expansive.

I had moved to Boulder five years before and set myself up as a calligraphic graphic designer, creating posters, brochures, logos and book covers that involved hand lettering. I was teaching calligraphy and book arts at Naropa University, collaborating with poets, musicians and storytellers in performance as well as taking on numerous buddhist calligraphic tasks like these vow certificates. I was part of a dynamic spiritual community, involved in interesting creative work, and valued for my skills.

All religious traditions have had a calligraphic element to their art. Medieval Christian monks wrote sacred texts on vellum. In Asian buddhist cultures monks copied out intricate sutras on palm leaves while Islamic calligraphers poured all their illustrative energy into maze-like letter forms. Calligraphy was an ancient contemplative act that synchronized mind and body on the spot, an embodied spiritual expression. Here I was, a modern day calligrapher, connected with an ancient religious tradition and teacher that valued this art form deeply.

The interview process was simple and distilled. (I had gone through the experience twice and been given the refuge name Turquoise Lake of Patience and bodhisattva name Dharma Cloud of Liberation.) Sometimes I was in the room when the interviews happened. A student would be ushered in and their name announced. Rinpoche was sitting at a table with his secretary nearby. The student would stand in front of him and Rinpoche would sometimes ask in his small soft voice, "How are you? " or " Why do you want to take this vow?" and a short dialogue might unfold. Usually not much was said. The space was resonant and full, with the sense of being seen, exposed. After the student left, Rinpoche would lean over to his secretary and tell him the dharma name in Tibetan and English and that would be noted down. The decision seemed to arise intuitively from the space of the relationship. When the interviews were over Rinpoche wrote the Tibetan characters for each name on sheets of paper and these would be laid out on tables to dry.

On this particular day our small team of calligraphers arrived in the afternoon and went to work adding the translations to the pages. Halfway through the task we received word that Rinpoche had decided to name a Court Calligrapher in a private ceremony. This would be happening soon. We were asked to come upstairs to A Suite for the presentation. So there I was, waiting in the hallway, secretly expecting this acknowledgement of my efforts and skill.

During these years the environment around Chögyam Trungpa was a complex interweaving of cultural elements. Traditional Tibetan buddhist texts were studied and chanted and ornate Tibetan imagery and decorations filled the shrine rooms. Many students were studying different Japanese art forms - ikebana flower arranging, Kyudo archery and chad tea ceremony. There was also a flavor of British aristocracy running through it all with men wearing elegant tailored suits and women in silk blouses, skirts and heels. Couples created tokanoma shrines for flower arrangements in their homes. They also owned silver tea sets and gave dinner parties with elaborate English place settings.

Trungpa had escaped from Tibet as a young monk in 1959, lived in India and then traveled to England where he had studied at Oxford and begun teaching meditation. During this period he took off his robes and married a young woman from an upper class family (who was referred to as Lady Diana). They moved to America in 1970 and it was here that he connected deeply with Shunryu Suzuki Roshi who was gathering his own community of American Zen practitioners in the Bay Area. There was a atmosphere of royalty in Rinpoche's household and organization that drew on both British and Japanese culture. Hearing that a Court Calligrapher was about to be named seemed appropriate and fitting.

Rinpoche's personal secretary came out into the hallway and invited us to enter. As we walked through the inner door she took me aside and said quietly that she wanted me to know that Rinpoche had decided to give the title to Robert. "We all know that you are the one who deserves it, but Rinpoche feels that Bob needs this more. I just wanted to alert you. " I nodded understandingly and walked into the room, standing at the edge and watching Rinpoche read the title and Bob stepping up to receive it. My body was wooden, my face a tight mask. I kept my gaze down, felt kicked in the core, devastated. All the work I had done and it was the wounded male who got the acknowledgement. I was furious.

The next morning I returned to the center to complete the calligraphies. Robert did not appear. I decided that he had been out drinking the night before. I took over the job and completed the task feeling smug, competent, protected.

Looking back I can see that I was too full to receive any acknowledgement. For me the teaching was in the holding back of confirmation. By not getting what I thought I deserved my demand towards the world was exposed. It would take some time for me to see this and soften.

I had written out a quote by Trungpa around that time.

It still hangs in my studio. I'm still working with it.

Openness is not a matter of giving something to someone else . . .

it means giving up your demand and the basic criteria of your demand . . .

it is learning to trust in the fact that you do not need to secure your ground,

learning to trust in your fundamental richness. . .

that you can afford to be open.

This is the open way.

-

I painted a peony flower once. It was in full bloom, opened up completely. Over many hours I drew the complexity of petals with pencil and filled in each one with soft watercolor washes in myriad tones of rose, an ongoing balancing act of control and letting go in the delicate dance of pigment and water and air. When I finished the painting I wrote the word peony below with black sumi ink in a stretched out and relaxed brush script.

I don't remember at what point I decided to give it to my buddhist teacher Chögyam Trungpa. Probably when it was complete and I could see the fullness of the creation. I wanted to give him a piece of my art as an expression of gratitude for his teachings that had opened my life. I wanted to give him something I was attached to, something that would stretch my generosity. And there was also a part that wanted to be seen.

So I made an appointment to meet with him.

This was 1986. My calligraphy studio was near the Vajradhatu administrative offices in Boulder. I rolled up the painting and walked down the street at the appointed time, entered the building and went up the central stairs to the second floor.

Rinpoche's secretary greeted and escorted me into the private office, spoke my name in introduction and then left, and it was just the two of us.

At this stage of his short and illuminated life Chögyam Trungpa was beginning to recede and contract. There was a quality of compression around him, his skin seemed darker, his eyes blacker, his presence more silent.

I stood in front of the desk where he was sitting. He looked up at me slowly, his deep liquid eyes visible over his glasses.

I bowed, still holding the package, and then said I had something I wanted to give him and I presented the painting, laying it out on the desk. He studied it silently. His body seemed small. The space in the room was thick, full, immovable. It was unbearable to just be with. I had to do something.

I walked around the desk and stood next to him facing the painting and began to talk - fast. I described how I had painted it petal by petal and then prepared to write peony and how nervous I had been at having only one shot at this. I explained that I had practiced writing the word a few times and then laid a ruler at the bottom to keep the paper steady and flat. Then I'd dipped the brush in the ink and on the first down stroke of the "p" my hand had hit against the ruler and it had felt like tripping at the beginning of running off a high dive but there was no turning back, I had to keep going, and the letters had fallen forth and landed and there it was.

I stopped talking. He was silent. We both looked at the peony.

After some moments he motioned for me to come around to his other side and I sat on a chair facing him. He slowly leaned forward. I leaned in too and our foreheads touched gently.

Heads bowed together he looked up at me from over his glasses and our eyes met. In a small high voice he said slowly, "We are going to be working together for a long time." I nodded yes.

A year later he was gone.

And I am continuing to work with him.

-

It was the early 1980’s in Boulder, Colorado. I was standing outside the front door of Dorje Dzong, the Tibetan Buddhist center, rearranging the posters inside the glass-cased bulletin board mounted outside the building. I felt some movement behind me so I turned and watched a group of seven people step through the door onto the covered landing where I was working. At the center was my teacher Chögyam Trungpa, moving slowly, limping slightly, his left arm supported by his attendant.

Rinpoche stopped on the landing and everyone stopped with him. I turned to face him and bowed slightly, standing up against the glass case. There was not much room to maneuver. Rinpoche asked what I was doing and I angled myself back to the case, pointing to the posters of upcoming events. He studied them silently.

I turned back to face him. There was an unspoken rule in the Buddhist community to never turn one’s back on the teacher. In this small transitional space we all continued to stand facing him, slightly bowed, waiting. The silence was big and awkward.

At a certain moment , it wasn’t a conscious decision, I broke the awkwardness for myself, turned to the bulletin board behind me, and went back to work. I needed to be free from the weight of holding still. I needed to return to my task. In a few moments I felt the collection of bodies move past me, down the stairs onto the street.

It was only afterwards that my mind caught up with what had happened. The intensity of the thoughts that arose had to have been linked to some deep wiring - a childhood embarrassment of doing something wrong when I was trying to be good. All I knew at the time was that I had broken a primary law of spiritual etiquette. I had turned away from my teacher.

Each time I remembered this moment over the next forty years I felt a wave of shame rise up inside. I didn’t tell anyone what I had done and no one who had been there ever mentioned the incident. Perhaps it had been barely noticed, except by my psyche where it held a powerful seat .

Recently I told the story of this encounter at the yearly anniversary marking Trungpa’s passing ( parinirvana ) . After all this time I realized the shame was gone. I saw the rightness in my action. I had acknowledged my teacher, shown respect, and gone back to work. How had this inner shift occurred ?

Over the years I had been part of Vajradhatu, the multi-leveled spiritual organization surrounding Trungpa. I was holding a role, trying to follow the complexity of unspoken yet powerful rules. I was learning how to create uplifted environments and potent community rituals. I was understanding the nature of decorum, how to behave properly. The need to belong wove through this deep community web. I was trying to be very good at it all.

Turning away in that moment was the seed , perhaps, of a change, of beginning to walk my own path. The projection on the teacher can be powerful, seeing them as perfect and enlightened, or imperfect when the teacher acts in a flawed way. Over the years some center had been building inside me that was gradually taking back both these projections and holding the perfect and imperfect within.

Chögyam Trungpa had marked me deeply with the freshness of his teachings and powerful presence. I have carried his mark inside and it continues to enrich my life. My conversation with him continues. .

There is the solo journey, wide yet vulnerable. There is also the protective embrace of community. I believe we move between these individual and collective paths throughout our lives. Perhaps we can even shift in a moment. When I turned away from my teacher I had moved to my solo way and was following my own true nature.